Understanding IFR Weather: AWOS-1, AWOS-2, and AWOS-3

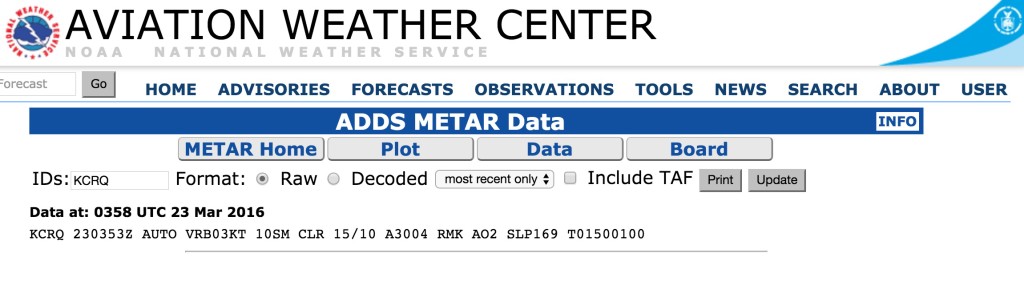

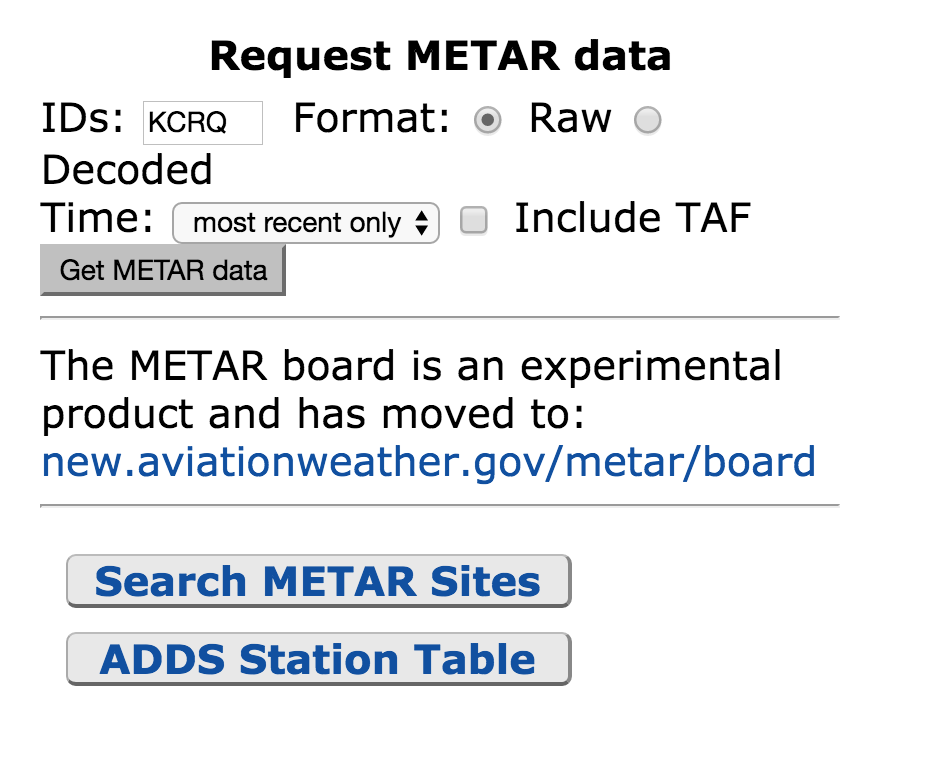

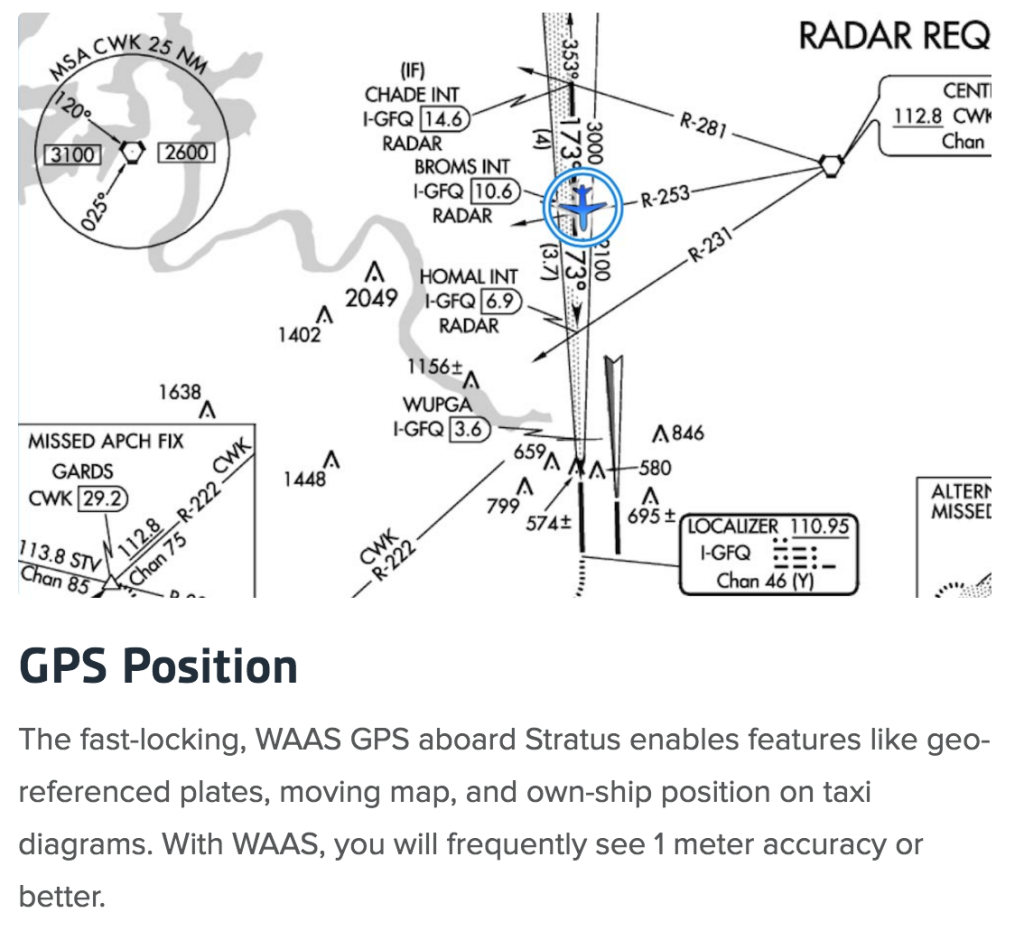

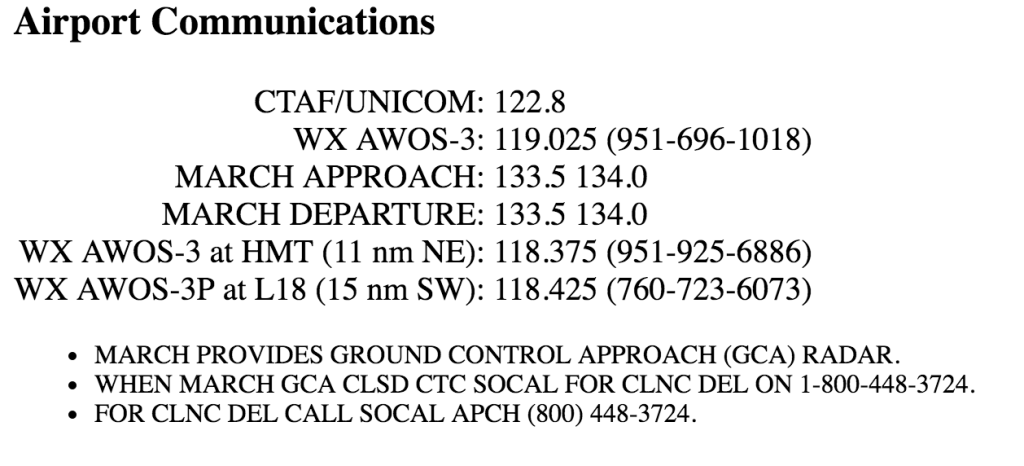

I know for the instrument checkride next month I will be asked about the different types of weather reporting. This is important to know, because as a pilot, you need to be able to not just interpret the weather, but also know what types of weather reports you need. At KCRQ (Carlsbad), there is an ATIS. At KOKB (Oceanside), there is an ASOS. F70 (French Valley) has an AWOS-3. So what’s an AWOS? AWOS stands for Automatic Weather Observation System. It is a unit that measures and reports local weather at an airport to pilots.

There are four basic levels of AWOS:

- AWOS-A: Reports only the altimeter setting.

- AWOS-1: Reports altimeter setting, wind data, temperature/dew point and density altitude.

- AWOS-2: Reports the information provided by AWOS-1, plus the visibility.

- AWOS-3: Provides the visibility provided by AWOS-2, plus cloud-ceiling data.

For Part 121 or 135 operators, AWOS-3 is the only type of AWOS that’s acceptable without restriction.

Instrument Checkride Prep: Reading Aviation Winds and Temperatures Aloft Forecasts

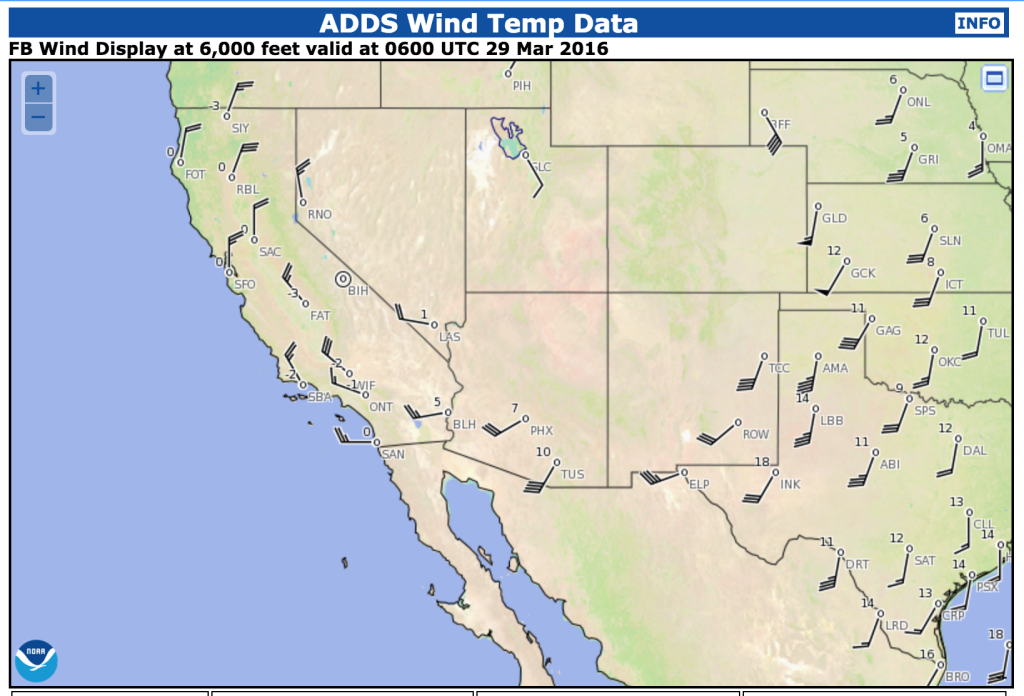

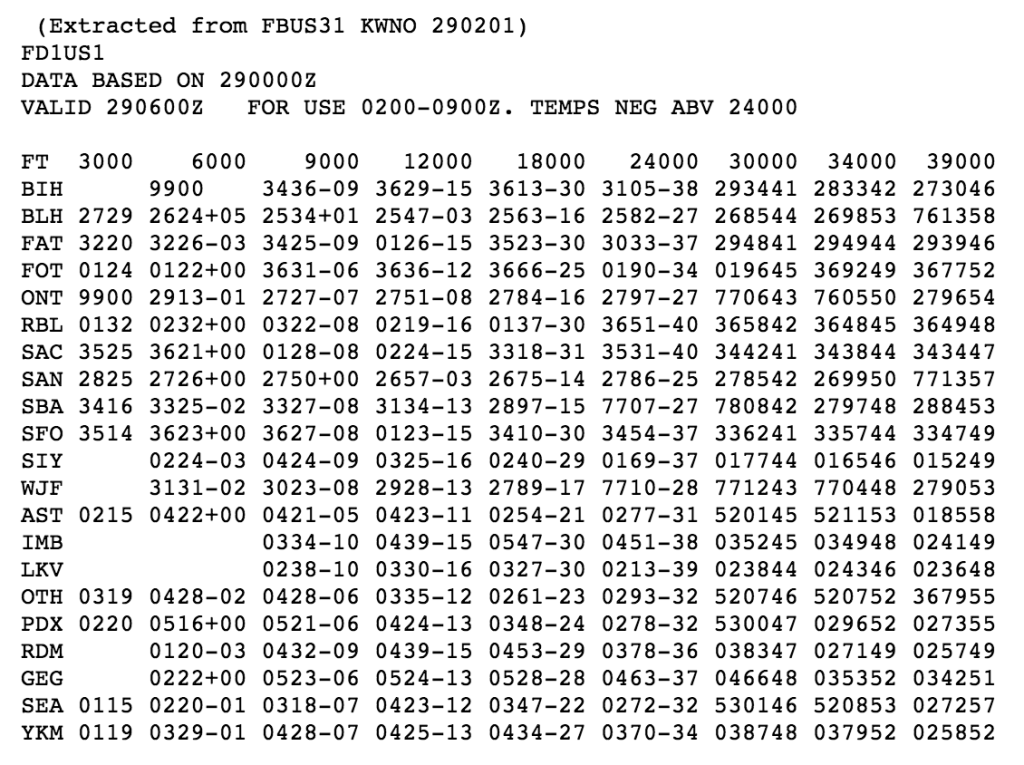

On the instrument check ride next month, I know the examiner will be asking me about the Wind & Temps Aloft forecast. This is issued 4 times daily for different altitudes and flight levels. The format is DIRECTION – SPEED – TEMPERATURE. If it says 9900 then that means light and variable. Wind direction is from true north, according to aviationweather.gov.

Things get a little tricky when the wind is is about 100 or 200 knots. Just remember “Between 51 and 86.”

When the wind speed is 100 knots or greater, wind direction is coded as a number between 51 and 86. And then you subtract 50 from that number – that’s your direction. And then you add 100 to the second set of numbers. That is your wind speed. Let’s practice:

“751950”

- Direction (75-50) Winds coming from 250°

- Speed (19 + 100) 119 knots

Above 24,000 feet, the temperature is assumed to be negative. If this forecast was issued at 34,000, you would assume the temperature to be negative 50 degrees.

Let’s try another one, from tonight’s forecast:

At 39,000 feet over SAN: “771357”

- Direction= (77-50) winds coming from 270°

- Speed = (13 + 100) 113 knots

- Temperature = -57 degrees

another one, just for fun. at 39,000 feet over BLH: “761358”

- Direction= (76-50) winds coming from 260°

- Speed= (13+100) 113 knots

- Temperature -58 degrees

All levels through 12,000 feet are true altitude (MSL). The levels 18,000 feet and above are pressure altitude.